The ethics of conflict resolution in south-east Sierra Leone

Abstract

Most conflict resolution literature focuses on strategic and tactical considerations, generally leaving aside psychological, and especially ethical, ones. Rapoport's Fights, Games and Debates is the notable exception and will be used to introduce satyagraha as a method of conflict resolution. The literature on law and society and the Gandhian literature are generally interlinked in political theory concerning civil disobedience but not in other areas such as interpersonal conflicts or the role of the legal system as a general mechanism of conflict resolution. This study aims at exploring these areas specifically and to look at the phenomenon of conflict and conflict resolution in the light of Gandhi's moral and ethical thought.

The Gandhian technique of conflict resolution is known by its Gujarati name of satyagraha which has variously been interpreted as "passive resistance", "nonviolent resistance", "nonviolent direct action", and even as "militant nonviolence".

"Satyagraha", Gandhi explained, is "literally holding on to Truth and it means, therefore, Truth-force. Truth is soul or spirit. It is therefore known as soul- force." The word was coined out of felt necessity. The technique of nonviolent struggle that Gandhi had evolved in South Africa for the conduct of the Indian indentured labourers' disputes with the government was originally described by the English phrase "passive resistance". Gandhi, however, found that the term "was too narrowly constructed, that it was supposed to be a weapon of the weak, that it could be characterised by hatred, and that it could finally manifest itself as violence."[1] He decided that a new word had to be coined for the struggle:

But I could not for the life of me find out a new name, and therefore offered a nominal prize through Indian Opinion to the reader who made the best suggestion on the subject. As a result, Maganlal Gandhi coined the word Sadagraha (sat: truth; Agraha: firmness) and won the prize. But in order to make it clearer I changed the word to Satyagraha.[2]

Satyagraha means, in effect, the discovery of truth and working steadily towards it, thus converting the opponent into a friend. In other words, satyagraha is not used against anybody but is done with somebody. "It is based on the idea that the moral appeal to the heart or conscience is . . . more effective than an appeal based on threat or bodily pain or violence."[3]

Over the years an enormous body of literature concerning satyagraha has developed. Generally the writings concern themselves with an examination of the various campaigns led either by Gandhi or his disciples, and, in the main, these writings clearly identify the main elements of the technique as truth (satya), nonviolence (ahimsa) and the relationship of ends to means. Most have realized that the use of the techniques of satyagraha as a policy, that is, a method to be brought into play in a given situation where it is considered effective in securing a victory, is contrary to its primary teaching. It must be a creed, a way of life, to be truly effective.

This work examines the ethics of conflict resolution in south-east Sierra Leone using the Gandhian ethics resolution framework. Chapter One deals with the theoretical framework of conflict, it defines conflict and examines its causes and the way it is generally handled. It also illustrates the behavior that leads conflict onto either productive or destructive paths as defined.

Chapter Two discusses the analytical framework for resolution generally and satyagraha specifically. It further examines satyagraha as a productive method of conflict resolution. Satyagraha is distinguished from other methods of nonviolent action and its main precepts are examined from the standpoint of the individual.

Chapter Three gives a background of the research work, giving a geo-linguistics breakdown of the people and the community. This work further examines the practical application of satyagraha in the light of the first two chapters.

Chapter Four briefly elucidates Gandhi's philosophy in action in the realm of interpersonal conflict in south-east Sierra Leone, while Chapter Five examines in some depth the possible practical application of satyagraha within our main institutionalised method of conflict resolution, namely the adversary legal system. It also examines industrial conflicts from the perspective of satyagraha.

Downloads

References

Ansbacher, H. L. and Ansbacher, R. R. (eds.), The Individual Psychology of Alfred Adler (Harper Torchbooks, New York, 1964).

Aubert, V., "Competition and Dissensus: Two Types of Conflict and of Conflict Resolution", Journal of Conflict Resolution, vol. 7, 1963, pp. .26-42.

---- , "Courts and Conflict Resolution", Journal of Conflict Resolution, vol. 11, 1967, pp. 40-51.

---- , "Law as a Way of Resolving Conflict: The Case of a Small Industrialized Society" in Nader (ed.), Law in Culture and Society, pp. 282-303.

Aziz, A., "Application Prospects of Gandhian Approach to Industrial Relations" in Das and Mishra (eds.), Gandhi in To-Day's India, pp. 139-57.

Barnes, H. E., An Existentialist Ethics (University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 1978).

Barnett, S. A., "On the Hazards of Analogies" in Montagu (ed.), Man and Aggression, pp. 75-83.

Bartos, O. J., "Determinants and Consequences of Toughness" in Swingle (ed.), The Structure of Conflict, pp. 45-68.

Bell, N. W., and Vogel, E. F. (eds.), A Modern Introduction to the Family (The Free Press, Glencoe, 111., 1960).

Belschner, W., "Learning and Aggression" in Selig (ed.), The Making of Human Aggression, pp. 61-103.

Benn, S. I. and Peters, R. S., "Human Action and the Limitations of Causal Explanations" in Edwards and Pap (eds.), A Modern Approach to Philosophy, pp. 94-8.

Bennett, J., "The Resistance Against German Occupation of Denmark 1940-5" in Roberts (ed.), The Strategy of Civilian Defence, pp. 154-72.

Bondurant, J. V. (ed.), Conflict: Violence and Nonviolence (Aldine-Atherton, Chicago, 1971).

----, Conquest of Violence: The Gandhian Philosophy of Violence, revised edition (University of California Press, Berkeley, 1967).

----, "Satyagraha Versus Duragraha: The Limits of Symbolic Violence" in Ramachandran and Mahadevan (eds.), Gandhi: His Relevance for our Times, pp. 99-112.

----, "The Search for a Theory of Conflict" in Bondurant (ed.), Conflict: Violence and Non-Violence, pp. 1-25.

Bose, N. K., "Gandhian Approach to Social Conflict and War" in Ray (ed.), Gandhi, India and the World: An International Symposium, pp. 261-69.

----, My Days with Gandhi (Orient Longman, New Delhi, 1971).

----, Selections from Gandhi, second edition (Navajivan, Ahmedabad, 1957).

----, Studies in Gandhism (Navajivan, Ahmedabad, 1972).

Bose, R. N., Gandhian Technique and Tradition in Industrial Relations (Research Division, All India Institute of Social Welfare and Business Management, Calcutta, 1956).

TRANSFER OF COPYRIGHT

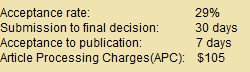

JRBEM is pleased to undertake the publication of your contribution to Journal of Research in Business Economics and Management.

The copyright to this article is transferred to JRBEM(including without limitation, the right to publish the work in whole or in part in any and all forms of media, now or hereafter known) effective if and when the article is accepted for publication thus granting JRBEM all rights for the work so that both parties may be protected from the consequences of unauthorized use.